Luke's Hand: Blade Runner

Watching Blade Runner with Cyborg Eyes

“Do you like our owl?” she inquires.

Right on cue, the fully grown Eurasian Eagle Owl dismounts its aniconic perch. A precise flutter fills the air as it glides supernaturally across a palatial hall, landing atop a symmetrically identical pedestal. It’s the closest brush with nature we’ve had in this gritty, hyper-artificial world. But it isn’t natural.

“It’s artificial,” Deckard responds casually.

“Of course it is,” Rachael confirms, as if there were no other option.

The scene feels primordial. Rachael prods Deckard about his profession, asking if he’d ever retired a human. Neo-Egyptian pillars frame the tableau as Tyrell, shrouded in shadow, emerges and surgically interjects:

“Capillary dilation—so-called Blush Response. Fluctuation of the pupil. Involuntary dilation of the iris.”

While the three characters metaphorically set the table, the owl watches from the shadows. Its eyes burn with a low amber glow—nearly the same hue as the sunset-washed room around it. Still. Silent. It watches—witness to the discomforting conversation below.

//surveillance mode: activeIf you’ve seen Blade Runner, or read its influential predecessor Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, you know the premise: a blade runner, Deckard, is tasked with locating and retiring (read: killing) a group of escaped replicants: android laborers nearly indistinguishable from their human counterparts. They seek their creator, Tyrell, in a desperate attempt to extend their four-year lifespan.

Retinal Glow

The owl in this scene gives viewers one of the film’s key tells: the glowing retina. Ridley Scott uses this detail to quietly flag artificial beings. If the eyes are the window to the soul, then the glow hints at something missing—a spiritual absence, perhaps. The lack of a true interior. It's a signature of artifice.

And yet, in that retinal glow resides a certain biting irony. Throughout Blade Runner, it’s the replicants who appear to feel more—more love, more fear, more hunger for meaning—than many of the humans we meet. This reversal gives unexpected depth to the Tyrell Corporation’s motto: “More human than human.” It lands not as pride, but as provocation.

A Recursive Test

The Voight-Kampff Test is an elaborate diagnostic device designed to detect empathy—or rather, the absence thereof. Tyrell’s previously mentioned commentary on blush response and iris dilation—it sets the stage. These involuntary physiological reactions form the foundation of the test, distinguishing humans from replicants.

// measure emotion using machine logicBut the irony deepens: the test is mechanical. The responses it hopes to induce are mechanical. In a world where emotion is the metric of humanity, both the tool and the criteria are coldly procedural. And colder yet is the edict to retire lost replicants.

“You know that Voight-Kampff test of yours…did you ever take that test yourself?” Rachael challenges Deckard in a moment of philosophical reckoning as she digests her newly revealed synthetic nature. We don’t get an answer, but we’re left to wonder: what if the human can’t pass the test?

Who or what is really under investigation here? Are the machines being tested, or is it humanity that is being challenged, even revealed?

J.F. Sebastian Makes Friends

J.F. Sebastian is a sympathetic and fascinating figure. In a twist of ironic fate, he takes in a struggling fugitive replicant from the street. As he leads her through the labyrinthine halls of his building, he casually mentions that he’s a genetic designer who reports directly to Tyrell. Occasionally, they even play chess.

Along the way, quirky toy soldiers and dolls spring to life. A stuffed bear with a tricorner hat and a doll-faced soldier, both no taller than children greet J.F. and his newfound replicant acquaintance, Pris. “They're my friends, I made them,” Sebastian notes as his robotic creations march around the unlikely pair.

It’s a proclamation. He doesn’t really have friends, so he makes them. Literally. His plight is at once so human, and yet it is aligned with the fate of the replicants. He suffers from a condition that causes rapid aging. He, like the replicants he’s helped bring to life, has a shortened and absolute lifespan.

His character also parallels notable historical figures who laid the foundation for our real-world technological embodiments. To the cyborg historian, J.F. Sebastian may stir up references to historical characters like Jacques de Vaucanson.

//origin protocol: mirrored.Vaucanson’s invention of the all-metal lathe and the automatic loom were keystones in the foundation of the Industrial Revolution. Just as influential, though, were his lifelike creations: mechanical automata. And while some of his countrymen found his dinner-serving, instrument-playing, and table-clearing automata fun and fascinating, one influential politician found his inventions “profane” and ordered the destruction of his workshop.

Since their inception, the unnatural qualities of automata and synthetic beings—like Sebastian’s friends, Tyrell’s replicants, and even Vaucanson’s automata—have unearthed fear and disgust among many observers. Whether represented by the judicial order to retire a no-longer-enslaved replicant in Blade Runner, or the destruction of Vaucanson’s workshop, humanity has long been threatened by the idea of living alongside its synthetic counterparts.

To Sebastian, the constructed are not just creations—they are friends. They understand him as much as he understands them.

A Quest for Identity

The central irony of Blade Runner lies not in its titular Blade Runner (don’t get me wrong, I love Harrison Ford), but in his targets: the replicants. Though manufactured, their struggle is the most human journey in the film. They show tenderness, fear, longing, and sacrifice. They want to live.

Rachael—Tyrell’s special replicant, the one who asks about the owl—faces an identity crisis. From the moment Deckard questions her humanity (“She doesn’t know, does she?” he remarks to Tyrell), she risks everything to find out: Am I real, or just a copy? Though she resists at first, Deckard reveals that her memories are not her own—they were implanted. But the feelings they stir are unmistakably real. She feels love. She feels confusion. And when her constructed memories unravel, she feels loss.

Roy Batty, the replicants’ leader, moves from rage to grace. His mission is to save his partner, whose time is running out. He pursues this with relentless urgency. But in the end, instead of letting Deckard fall to his death, Roy chooses to save him. In that choice, he transcends programming. He embraces empathy. He leaves a legacy—a final act of freedom.

The point is: it doesn’t really matter whether they’re made. They build meaning through experience. Even Rachael’s identity isn’t inherited. It’s assembled. Through trial. Through pain. Through connection.

For all of them, life is precious. As fragile—and as flammable—as J.F. Sebastian’s matchstick man.

Beings, Made

Blade Runner is a beloved film—campy to some, endlessly rewatchable to others. But there’s no doubt it’s cemented its place in the cyborg canon. Why?

It’s an aesthetic masterpiece. A cinematic touchstone. But it also raises a bigger question: if something is designed, does that make it less authentic? Less real?

And in true cyborg fashion, Ridley Scott refuses to answer that directly. Instead, he blurs the lines—rearranging our expectations about what it means to be natural, whole, or worthy.

Just as being made doesn’t disqualify you from feeling or choice, being born doesn’t guarantee empathy. Wholeness may be less about origin—and more about attention, awareness, and intention.

// human ≠ humaneRachael is made. Roy is made. Sebastian makes friends. And Deckard—he’s made by his work. So are we, in a way—shaped by our systems, our tools, our memories, our networks.

I like to think of Blade Runner as a dare. A dare to ask: is design a flaw? A threat to authenticity? Or is it part of the architecture of self?

And that owl?

It’s still. Still there. Still watching.

Eyes glowing—amber and gold.

“Do you like our owl?”

Yes. I do. Isn’t it beautiful?

Isn’t it alive, in its own way?

// end transmissionLuke’s Hand is a series about designed identity, constructed selves, and the quiet feedback loops between what we make and what makes us. It explores the porous boundary between human and machine through explorations in popular sci-fi culture and media: film, books, videogames and more.

This is the first entry in the Luke’s Hand series, exploring cyborg theory and selfhood through cinema. I’m sharing this one with everyone—it’s public for now—but future entries in the series may be for paid subscribers. If it resonates, I’d love to have you along for the journey.

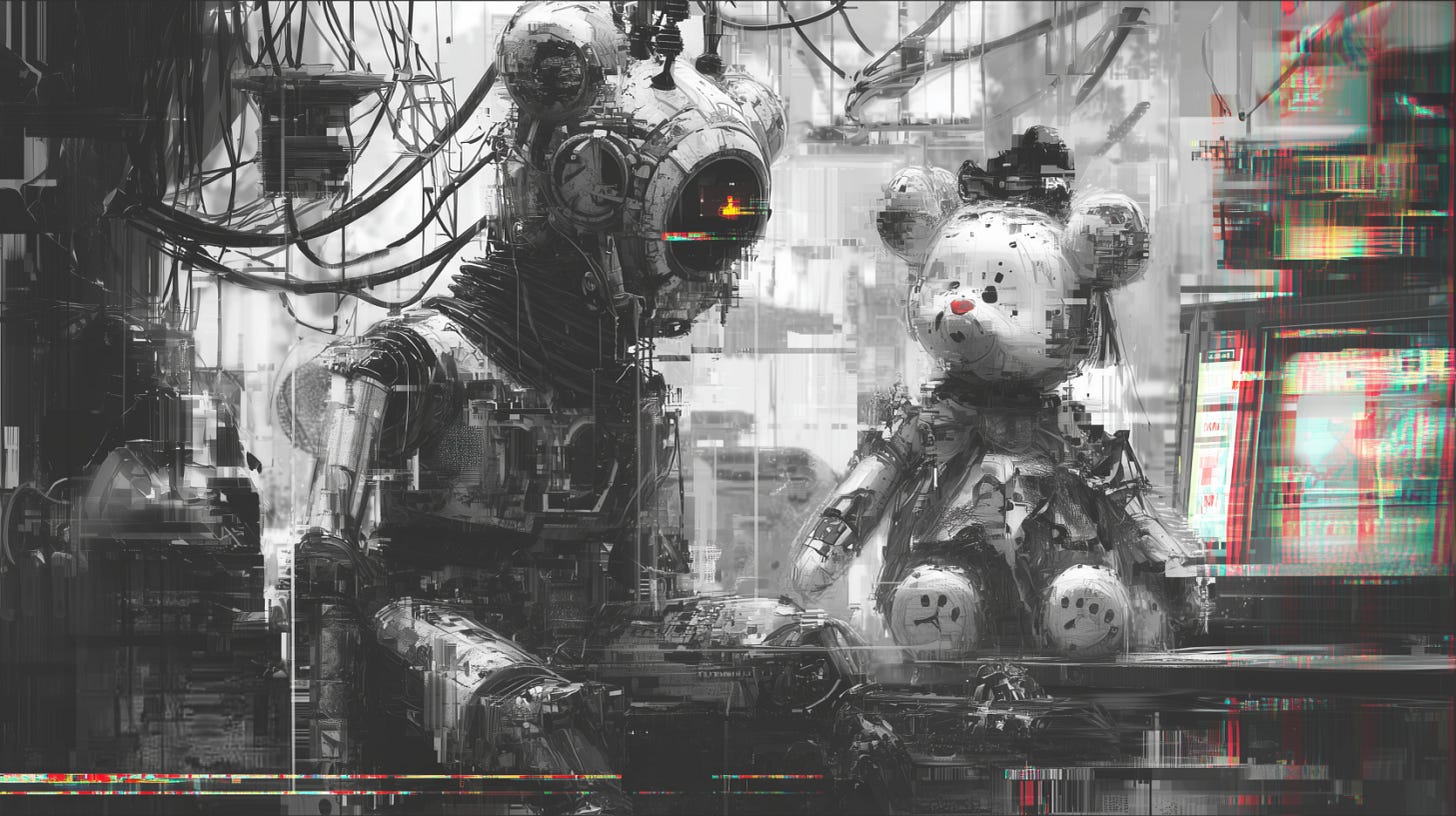

Illustrations by PL4S7IK. Generated and refined through cyborg collaboration — Midjourney prompting (co-developed with ChatGPT and human directorial chaos), Photoshop layering, Procreate detailing, and plenty of human signal shaping the static. https://linktr.ee/Pl4s7ik